Privacy Policy | Terms of Use | Cookie Policy | Disclaimer

Empowering the American middle class — one story at a time.

Rebuilding and Reform

After the Civil War ended in 1865, America faced one of its most complex and challenging periods: Reconstruction. The Union may have been preserved, but the social and economic wounds of slavery and war were deep. The federal government took bold steps to rebuild the South and integrate millions of newly freed African Americans into society. Amendments were added to the Constitution granting citizenship and voting rights to former slaves. Yet, the road to real equality was steep and riddled with resistance.

During Reconstruction, the Freedmen’s Bureau was created to support newly emancipated individuals with food, housing, education, and legal assistance. Schools were built, and African Americans were elected to public office for the first time. But progress was met with backlash. White supremacist groups rose in opposition, and new laws, known as Jim Crow laws, began to enforce segregation and restrict Black civil rights — particularly in the South.

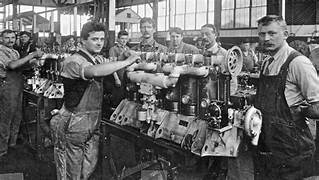

As the country pushed into the Gilded Age, a new wave of reform began to take shape. The rise of industrialization brought tremendous economic growth, but also increased inequality, exploitation of workers, and unsafe working conditions. Children labored in factories, wages were low, and workdays stretched well beyond ten hours. These injustices gave birth to organized labor movements such as the American Federation of Labor, which demanded better conditions, fair wages, and dignity for workers.

Simultaneously, a wave of immigration from Europe transformed the social fabric of cities. While these new arrivals provided labor that fueled the economy, they also faced discrimination and poor living conditions. Reformers like Jane Addams, who established Hull House in Chicago, stepped forward to offer education, healthcare, and housing to immigrant communities. These were early examples of social work and community-based activism.

Women's rights also surged during this time. Led by visionaries like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, women began demanding the right to vote and full participation in democracy. The suffrage movement would ultimately culminate in the 19th Amendment in 1920, but its roots were planted during these critical years of national reform.

Muckraking journalists like Upton Sinclair and Ida Tarbell exposed corruption, unsafe food production, and monopolistic business practices. Their work fueled the Progressive Era, which saw Presidents like Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson implement regulations that protected the public and held corporations accountable.

"Every man holds in his hands the power to mold the world." — Susan B. Anthony

This era also laid the foundation for the American middle class. As reforms were slowly enacted — including antitrust laws, minimum wage standards, and labor protections — more families began to rise out of poverty. Public education expanded. The idea that the average American could own a home, work a stable job, and raise a family became more than a dream — it became a national goal.

Rebuilding and reform were not only about restoring what was lost, but reimagining what America could become. The country learned that progress often comes from the voices of ordinary people rising up against injustice. These movements — though imperfect and unfinished — represent the will of citizens to shape their government, their economy, and their future.

The legacy of this period lives on in today’s middle class, which continues to benefit from the hard-won victories of those who came before. It reminds us that progress is always possible when people are willing to stand up, speak out, and work together for a better tomorrow.